“Hate speech” is an umbrella term covering a range of hateful behaviour, from stirring up racism to actively promoting genocide. While the phrase itself is relatively new, the basic concept can be traced back to the immediate aftermath of World War II.

Following the prosecution of leading Nazis at Nuremberg, the United Nations created a series of international agreements which aimed to prevent a repeat of the Holocaust, and build a world in which all human rights are respected.

From its earliest years, the United Nations has recognised that certain types of hateful speech must be tackled:

- The 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide called for “direct and public incitement to commit genocide” to be legally prohibited.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, signed the same year, spelled out that “All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination… and against any incitement to such discrimination”.

- The 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination committed member countries to “declare an offence punishable by law all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination” and prohibit “propaganda activities, which promote and incite racial discrimination”.

- The 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights stipulated that “advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law”.

Since World War II, many countries – including the UK – have introduced national laws which criminalise some forms of incitement. The following types of hateful rhetoric are also widely seen as problematic, even when they don’t cross a legal line:

- Demonisation: Presenting the target group (often but not always a minority) in overwhelmingly negative terms – characterising them as inherently malicious, dishonest or threatening.

- Toxic misinformation: False stories linking the target group to violent, criminal or morally corrupt behaviour.

- Dehumanisation: Portraying the target group as subhuman – likening them to vermin, parasites or disease.

- “Accusation in a mirror”: Claiming that the target group is conspiring to attack the wider population, and poses an existential threat.

These types of hateful speech are regarded as dangerous because, over time, they can create a climate in which the group is more likely to face discrimination, aggression and abuse, even if the call for violence is not made explicit.

Although the main focus within international law has been on racial and religious hatred, modern definitions of hate speech generally include all protected characteristics, including sexual orientation, national origin, disability, sex, gender identity and intersex status.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has defined hate speech in these terms:

“In national and international legislation, hate speech refers to expressions that advocate incitement to harm (particularly, discrimination, hostility or violence) based upon the target’s being identified with a certain social or demographic group. It may include, but is not limited to, speech that advocates, threatens, or encourages violent acts. For some, however, the concept extends also to expressions that foster a climate of prejudice and intolerance on the assumption that this may fuel targeted discrimination, hostility and violent attacks.”

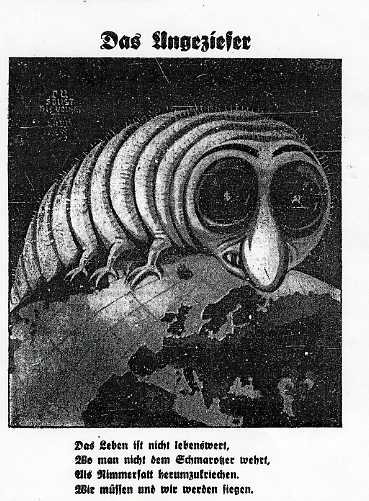

Demonisation, dehumanisation and incitement – the case of Der Stürmer

While not every article in Streicher’s newspaper had passed the criminal threshold, the court also recognised that “In his speeches and articles, week after week, month after month, he infected the German mind with the virus of anti-Semitism”.

Streicher founded Der Stürmer in 1923. Yet the calls for extermination didn’t start immediately. Instead, the newspaper began by demonising Jews through a regular drip-drip of negative stories, including sensationalist reports of violent sexual crimes, and attacks on children, which it claimed had been committed by Jewish people.

Der Stürmer also dehumanised Jews by portraying them as snakes, rats, maggots and other vermin. Over time, Streicher’s newspaper sought to normalise the idea that Jewish people were less than human, and fundamentally different in character from other Germans.

Then from the 1930s onwards, the newspaper began regularly calling for Jews to be murdered. In doing so, Streicher presented Jews as an existential threat, including claims of a “Jewish murder plan against Gentile humanity”.

In the words of the Nuremberg prosecutors: “Through propaganda designed to incite hatred and fear, defendant Streicher devoted himself, over a period of twenty-five years, to creating the psychological basis essential to carrying through a program of mass murder”.

Dehumanising hate speech – and the deadly power of a metaphor

Many of the techniques used in Nazi Germany to incite hatred against Jews have also been applied elsewhere. During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, media outlets fuelled hatred towards the Tutsi minority by likening them to “cockroaches” and “snakes”. More recently in Myanmar, extremists have fomented mass-violence against Rohingya Muslims by characterising them as “snakes” and “worse than dogs”.

The Dangerous Speech project argues that dehumanisation is especially harmful because as humans “we do not simply talk in metaphors, but we also think and feel in terms of them… when we come across a metaphor, it can shape our ideas strongly without us being aware of it”. The rhetoric of “snakes”, “cockroaches” and “vermin” evokes “hostility, disdain… physical disgust, and/or bodily fear”. According to Dangerous Speech, such metaphors encourage people to see the target group as “obnoxious, disease carrying, and/or bloodthirsty creatures that should be removed… from the community”.

Dehumanisation has been so widespread in cases of mass-atrocity, that Genocide Watch has identified it as one of the 8 Stages of Genocide – and a warning sign that violence may be imminent.

Tackling hatred is a task for the whole of society. Only the most extreme hate speech is criminalised – and in many cases a non-legal response may be more appropriate.

In 2012, the United Nations put together the Rabat Plan of Action, a set of principles for identifying and tackling hate speech while also protecting legitimate free expression.

This acknowledges that “legislation is only part of a larger toolbox”, and that there will be examples of “expression that does not give rise to criminal, civil or administrative sanctions, but still raises concern in terms of tolerance, civility and respect for the rights of others”.

Hate speech laws should therefore, according to the UN, be accompanied by initiatives “creating and strengthening a culture of peace, tolerance and mutual respect” and “rendering media organizations and religious/community leaders more ethically aware and socially responsible.”

The UN’s Rabat Plan of Action spells out that tackling hate speech is not just a job for governments alone. On the contrary, “states, media and society have a collective responsibility to ensure that acts of incitement to hatred are spoken out against and acted upon with the appropriate measures”.

Challenging hate within the UK media

As long ago as 2010, experts were warning that inflammatory UK media coverage was fuelling a rise in anti-Muslim hate crime.

In 2012, the Leveson Inquiry into UK press standards concluded: “there are enough examples of careless or reckless reporting to conclude that discriminatory, sensational or unbalanced reporting in relation to ethnic minorities, immigrants and/or asylum seekers is a feature of journalistic practice in parts of the press, rather than an aberration.”

Then in 2015, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, issued a statement condemning “decades of sustained and unrestrained anti-foreigner abuse, misinformation and distortion” in the UK press.

The High Commissioner’s immediate concern was an article in the Sun newspaper likening African migrants to “cockroaches”, describing migrants as “a plague of feral humans”, and comparing them to “a norovirus”.

Al Hussein highlighted that: “The Nazi media described people their masters wanted to eliminate as rats and cockroaches. This type of language is clearly inflammatory and unacceptable, especially in a national newspaper”.

But he also pointed out that this was “simply one of the more extreme examples of thousands of anti-foreigner articles that have appeared in UK tabloids over the past two decades.”

According to the High Commissioner: “Asylum seekers and migrants have, day after day, for years on end, been linked to rape, murder, diseases such as HIV and TB, theft, and almost every conceivable crime and misdemeanour imaginable… Many of these stories have been grossly distorted and some have been outright fabrications”.

The UN statement concluded with a chilling warning: “History has shown us time and again the dangers of demonizing foreigners and minorities, and it is extraordinary and deeply shameful to see these types of tactics being used in a variety of countries, simply because racism and xenophobia are so easy to arouse in order to win votes or sell newspapers”.

The Sun’s article was reported to the UK police for incitement to racial hatred, but no charges were brought – again highlighting the difficulty of effectively challenging hate speech that falls short of crossing into criminal incitement.

The UN’s intervention was nonetheless a wake-up call for many in Britain, and contributed to the thinking which led to the launch of the Stop Funding Hate campaign in 2016.

The core idea behind Stop Funding Hate is that engaging with advertisers can help make hate unprofitable by reducing the financial incentives for publishing and inflammatory and divisive stories.

While there is still a long way to go, there has been a significant reduction in anti-migrant front pages in the UK press since Stop Funding Hate was launched.

In 2018, the Daily Mail newspaper revealed plans to “detoxify” after a string of advertisers pulled out following pressure from Stop Funding Hate supporters. There have also been changes at the Sun and Daily Express, the two other newspapers originally featured in the campaign.

At a UK Parliamentary hearing in 2018, the Sun’s Managing Editor publicly apologised for the article which had led to the newspaper being called out by the UN, saying:

“We can cherish freedom of expression, but using language like “cockroaches” is certainly not appropriate and I apologise for that.”

Consumer engagement with advertisers can be an “appropriate measure” for challenging hate speech that doesn’t cross a legal line but is still harmful

There is now a growing global movement of people pushing back against hate through consumer engagement with advertisers. In the United States, over 4,000 advertisers have withdrawn from the controversial website Breitbart following pressure from the Sleeping Giants campaign. Sleeping Giants also have active chapters challenging media hate in France, Germany, Australia, and elsewhere.

There’s an increasing recognition that this model of campaigning can be part of society’s “larger toolbox” for tackling hate speech which may not cross a legal line but is still problematic.

Most major advertisers want to appeal to as wide a customer base as possible. So they have sound commercial reasons not to alienate consumers by advertising with media that fuel hatred towards a particular group – even when that behaviour falls short of breaking the law.

While there are good grounds for governments to tread carefully in their application of hate speech laws, private companies are free to choose where they advertise according to any criteria they like. Consumers, too, are free to speak out and seek to influence those advertising choices.

Encouraging big brands to withdraw advertising can be an “appropriate measure” – to cite the UN’s words in the Rabat Plan of Action – for responding to hateful speech which “does not give rise to criminal, civil or administrative sanctions, but still raises concern in terms of tolerance, civility and respect for the rights of others”.

By applying a basic ethical standard in determining where they advertise, companies can help to create a “culture of peace, tolerance and mutual respect”, and encourage media outlets to report more responsibly.

Online Hate Speech

Just as in the 20th century newspapers and radio were used to fuel hatred and violence, in recent years the internet has increasingly been weaponised for the same purpose.

Across the world, Facebook and other tech platforms have been manipulated by extremists to spread hateful and divisive messages.

In 2018, Facebook was called out by the United Nations over the use of its systems to incite genocide against the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar. A recent study by researchers at the University of Warwick also found a strong correlation between Facebook usage and violence against refugees in Germany.

As with the print press, social media posts that provoke strong emotions are more likely to be picked up and shared – whether they’re true or false. The issue of online hate is often closely linked with that of hateful content in the traditional media: An inflammatory anti-migrant story from the Daily Mail or Fox News can reach a much larger audience when shared online.

But there are two in-built features of social media which can further amplify hateful content:

The tendency for tech platforms to a) automatically boost posts that are going “viral” and b) promote posts to particular users which are similar to material that they’ve previously engaged with. So a viral story fuelling hatred towards Muslims may be actively boosted – and automatically targeted at users who have previously shared similar material – further reinforcing negative views.

And as with the print press, advertising revenue plays a significant role: By designing their systems to automatically promote viral content, social media companies can keep their users engaged for longer, and so maximise their income from online advertising.

Between them, Facebook and Google (which owns Youtube) now receive almost 25% of global advertising revenue. But they are also facing increasing pressure – including from advertisers – to clean up their platforms and develop more effective processes for removing hate speech.